The narrow margin of the last presidential election left those on the losing side second-guessing themselves. Many of them blamed the loss on the opposition's appeals to Christian voters and their own candidate's failure to answer basic questions about his personal faith. Determined to win the next election, party strategists mapped plans to neutralize the religion issue. Those plans included buffing their candidate's image as a believer, condemning the other party's ties to evangelical extremists and hailing their side's devotion to religious liberty.

The narrow margin of the last presidential election left those on the losing side second-guessing themselves. Many of them blamed the loss on the opposition's appeals to Christian voters and their own candidate's failure to answer basic questions about his personal faith. Determined to win the next election, party strategists mapped plans to neutralize the religion issue. Those plans included buffing their candidate's image as a believer, condemning the other party's ties to evangelical extremists and hailing their side's devotion to religious liberty.It may sound like the current presidential campaign, but the year was 1800 and the beleaguered candidate was Thomas Jefferson. Four years earlier, he had lost the presidency to John Adams in an election fraught with religious angst. Jacobin revolutionaries had taken over France, closed its churches and threatened to export their reign of terror. Supporters of Adams' Federalist Party linked Jefferson to the French secularists through his defense of revolutionary France and support for the separation of church and state. Adams, in contrast, they argued, was a man of God who opposed radical French ideas, and under his rule America had launched a naval war with France and mobilized against a rumored Jacobin invasion.

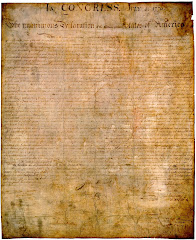

As the election of 1800 approached, a boldface notice appeared in leading Federalist newspapers. "At the present solemn and momentous epoch," it declared, "the only question to be asked by every American, laying his hand on his heart, is, 'Shall I continue in allegiance to GOD--AND A RELIGIOUS PRESIDENT; or impiously declare for JEFFERSON--AND NO GOD!!!'"

Such tactics had worked in 1796, but this time Jefferson's supporters rushed to his defense. In their party publications, they characterized Jefferson as "an adorer of our God" and "a real Christian." They wooed disaffected Protestants, Catholics and Jews by contrasting their candidate's defense of religious pluralism with Adams' purported support for an evangelical establishment. And turning the tables on their accusers, they also questioned Adams' faith. Despite his bow to civil religion by invoking God's name on public occasions, Adams differed little from Jefferson in his personal beliefs. Both men inclined toward Deism or Unitarianism, though Adams kept it under wraps better than Jefferson did. With both candidates sullied, their partisans debated the relative merits of a pious hypocrite vs. a reputed infidel as President.

Then, as now, many Christians saw biblical beliefs as the foundation for law and liberty. "If our religion were gone, our state of society would perish with it," declared Jefferson's chief evangelical critic, Yale president Timothy Dwight. The Jeffersonians bit back. "Now I don't know that John Adams is a hypocrite, or Jefferson a Deist," one wrote, "yet supposing they are, I am of the opinion the last ought to be preferred to the first [because] a secret enemy is worse than an open and avowed one."

The dueling charges largely neutralized the religion issue, which was all Jefferson needed, given public concerns over other Federalist policies. Both political parties reached out to Christian voters. Federalists praised Adams' public support for religious institutions; their opponents trumpeted Jefferson's passion for religious liberty. Each side claimed its candidate was a Christian--or at least as good a Christian as the other guy. By all accounts, Evangelicals still voted overwhelmingly for Adams but not in sufficient numbers to overcome the popular surge for Jefferson's party, which captured the presidency and both houses of Congress. Adams later blamed his defeat on fears that he was too tied to Evangelicals.

Today's Democratic Party appears to be taking a page from Jefferson's playbook by contesting the religious vote. In 2006 Democrats successfully ran an ordained minister for Ohio Governor against Ken Blackwell, a darling of the religious right, and a pro-life Catholic for Senator in Pennsylvania against fellow Catholic Rick Santorum. Now, as the numerous public declarations of faith made during this campaign season suggest, the party's leading candidates for President seem to have learned this lesson too and are, no doubt, praying for a similar outcome.

Larson is the author of A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800, America's First Presidential Campaign