Gore Vidal, one of the master stylists of American literature and one of the most acute observers of American life and history, turns his immense literary and historiographic talent to a portrait of the formidable trio of George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.

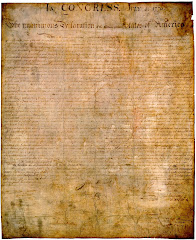

Gore Vidal, one of the master stylists of American literature and one of the most acute observers of American life and history, turns his immense literary and historiographic talent to a portrait of the formidable trio of George Washington, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.In Inventing a Nation, Vidal transports the reader into the minds, the living rooms (and bedrooms), the convention halls, and the salons of Washington, Jefferson, Adams, and others. We come to know these men, through Vidal’s splendid and percipient prose, in ways we have not up to now—their opinions of each other, their worries about money, their concerns about creating a viable democracy. Vidal brings them to life at the key moments of decision in the birthing of our nation. He also illuminates the force and weight of the documents they wrote, the speeches they delivered, and the institutions of government by which we still live. More than two centuries later, America is still largely governed by the ideas championed by this triumvirate.

Gore Vidal, novelist, essayist, and playwright, is one of America’s great men of letters. Among his many books are United States: Essays 1951-1991 (winner of the National Book Award), Burr: A Novel, Lincoln, and the recent Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace.

Book Excerpt

On September 5, 1774, forty-five of the weightiest colonial men formed the First Continental Congress at Philadelphia. The weightiest of the lot was the Boston lawyer John Adams, known as the best-read man in Boston. Short, fat, given to bouts of vanity that alternated with its first cousin self-pity, he was thirty-nine years old when he joined the Massachusetts delegation to the Congress. He was married to Abigail Smith, a marriage somewhat similar to that of his father, John the farmer, to Susanna Boylston. Each Adams had seemed instinctively to be obeying an old law of new societies, by marrying above his social station: farmer John to a Boylston, while Abigail’s mother was a storied Quincy.

The one who moves up is known as a hypergamist and, not too surprisingly, such marriages tend to be happier than classic love matches between like-stationed couples. Certainly, Abigail and John were the most interesting couple among the founders of the embryo nation, and their letters to each other are still a joy to read; nor were they alone in their marital adventurousness; even the protocolossus, Washington, had condescended to marry a grand fortune.

If Adams was the loftiest of the scholars at the Continental Congress of 1775, Thomas Jefferson was the most intricate character, gifted as writer, architect, farmer—and, in a corrupt moment, he allowed his cook to give birth to that unique dessert later known as Baked Alaska. Like Adams, he had tried his hand at constitution making in the spring of 1776. He sent A Summary View of the Rights of British America to Patrick Henry, the orator and professional Virginia politician, but got no answer. Henry reputedly had a problem with laudanum, the drug of the day. Jefferson was not pleased with this rebuff: "Whether Mr. Henry disapproved the ground taken," he later wrote, "or was too lazy to read it (for he was the laziest man in reading I ever knew) I never learned but he communicated it to nobody."

From April 1775 to July 1776 the undeclared war between England and its American colonies smoldered; flared up; appeared to sputter out... It was hardly, ever, a mass rebellion. For one thing, sixteen percent of the Americans were Tories: that is, loyalists to the crown. They were also among the wealthiest and best-educated of the colonists. Over the next eight years, as rebellion became war, many of them fled to Canada or even "back" to England, giving the radical lawyers who had taken charge of the Revolution a lucrative practice settling scores, not to mention estates.

Excerpt from Chapter 2 of Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Copyright 2003 Gore Vidal.